In this proof we (finally!) finish the proof of case one.

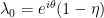

As usual, we throughout fix a nonstandard natural  and a complex polynomial of degree

and a complex polynomial of degree  whose zeroes are all in

whose zeroes are all in  . We assume that

. We assume that  is a zero of

is a zero of  whose standard part is

whose standard part is  , and assume that

, and assume that  has no critical points in

has no critical points in  . Let

. Let  be a random zero of

be a random zero of  and

and  a random critical point. Under these circumstances,

a random critical point. Under these circumstances,  is uniformly distributed on

is uniformly distributed on  and

and  is almost surely zero. In particular,

is almost surely zero. In particular,

and  is infinitesimal in probability, hence infinitesimal in distribution. Let

is infinitesimal in probability, hence infinitesimal in distribution. Let  be the expected value of

be the expected value of  (thus also of

(thus also of  ) and

) and  its variance. I think we won’t need the nonstandard-exponential bound

its variance. I think we won’t need the nonstandard-exponential bound  this time, as its purpose was fulfilled last time.

this time, as its purpose was fulfilled last time.

Last time we reduced the proof of case one to a sequence of lemmata. We now prove them.

1. Preliminary bounds

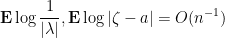

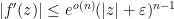

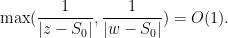

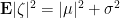

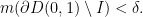

Lemma 1 Let  be a compact set. Then

be a compact set. Then

uniformly for  .

.

Proof: It suffices to prove this for a compact exhaustion, and thus it suffices to assume

By underspill, it suffices to show that for every standard  we have

we have

We first give the proof for  .

.

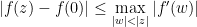

First suppose that  . Since

. Since  is infinitesimal in distribution,

is infinitesimal in distribution,

here we need the  and the

and the  since

since  is not a bounded continuous function of

is not a bounded continuous function of  . Since

. Since  we have

we have

but we know that

so, solving for  , we get

, we get

we absorbed a  into the

into the  . That gives

. That gives

Since  is a polynomial of degee

is a polynomial of degee  and

and  is monic (so the top coefficient of

is monic (so the top coefficient of  is

is  ) this gives a bound

) this gives a bound

even for  .

.

Now for  , we use the bound

, we use the bound

to transfer the above argument.

2. Uniform convergence of

Lemma 2 There is a standard compact set  and a standard countable set

and a standard countable set  such that

such that

all elements of  are isolated in

are isolated in  , and

, and  is infinitesimal.

is infinitesimal.

Tao claims

where  is a large standard natural, which makes no sense since the left-hand side should be large (and in particular, have positive standard part). I think this is just a typo though.

is a large standard natural, which makes no sense since the left-hand side should be large (and in particular, have positive standard part). I think this is just a typo though.

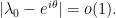

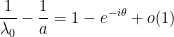

Proof: Since  was assumed far from

was assumed far from  we have

we have

We also have

so for every standard natural  there is a standard natural

there is a standard natural  such that

such that

Multiplying both sides by  we see that

we see that

where  is the variety of critical points

is the variety of critical points  . Let

. Let  be the set of standard parts of zeroes in

be the set of standard parts of zeroes in  ; then

; then  has cardinality

has cardinality  and so is finite. For every zero

and so is finite. For every zero  , either

, either

- For every

,

,

so the standard part of  is

is  , or

, or

- There is an

such that

such that  is infinitesimal.

is infinitesimal.

So we may set  ; then

; then  is standard and countable, and does not converge to a point in

is standard and countable, and does not converge to a point in  , so

, so  is standard and

is standard and  is infinitesimal.

is infinitesimal.

I was a little stumped on why  is compact; Tao doesn’t prove this. It turns out it’s obvious, I was just too clueless to see it. The construction of

is compact; Tao doesn’t prove this. It turns out it’s obvious, I was just too clueless to see it. The construction of  forces that for any

forces that for any  , there are only finitely many

, there are only finitely many  with

with  , so if

, so if  clusters anywhere, then it can only cluster on

clusters anywhere, then it can only cluster on  . This gives the desired compactness.

. This gives the desired compactness.

The above proof is basically just the proof of Ascoli’s compactness theorem adopted to this setting and rephrased to replace the diagonal argument (or 👏 KEEP 👏 PASSING 👏 TO 👏 SUBSEQUENCES 👏) with the choice of a nonstandard natural. I think the point is that, once we have chosen a nontrivial ultrafilter on  , a nonstandard function is the same thing as sequence of functions, and the ultrafilter tells us which subsequences of reals to pass to.

, a nonstandard function is the same thing as sequence of functions, and the ultrafilter tells us which subsequences of reals to pass to.

3. Approximating  outside of

outside of

We break up the approximation lemma into multiple parts. Let  be a standard compact set which does not meet

be a standard compact set which does not meet  . Given a curve

. Given a curve  we denote its arc length by

we denote its arc length by  ; we always assume that an arc length does exist.

; we always assume that an arc length does exist.

A point which stumped me for a humiliatingly long time is the following:

Lemma 3 Let  . Then there is a curve

. Then there is a curve  from

from  to

to  which misses

which misses  and satisfies the uniform estimate

and satisfies the uniform estimate

Proof: We use the decomposition of  into the arc

into the arc

and the discrete set  . We try to set

. We try to set  to be the line segment

to be the line segment ![{[z, w]}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5Bz%2C+w%5D%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) but there are two things that could go wrong. If

but there are two things that could go wrong. If ![{[z, w]}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5Bz%2C+w%5D%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) hits a point of

hits a point of  we can just perturb it slightly by an error which is negligible compared to

we can just perturb it slightly by an error which is negligible compared to ![{[z, w]}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5Bz%2C+w%5D%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) . Otherwise we might hit a point of

. Otherwise we might hit a point of  in which case we need to go the long way around. However,

in which case we need to go the long way around. However,  and

and  are compact, so we have a uniform bound

are compact, so we have a uniform bound

Therefore we can instead consider a curve  which goes all the way around

which goes all the way around  , leaving

, leaving  . This curve has length

. This curve has length  for

for  close to

close to  (and if

(and if  are far from

are far from  we can just perturb a line segment without generating too much error). Using our uniform max bound above we see that this choice of

we can just perturb a line segment without generating too much error). Using our uniform max bound above we see that this choice of  is valid.

is valid.

Recall that the moments  of

of  are infinitesimal.

are infinitesimal.

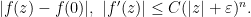

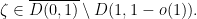

Since  is infinitesimal, and

is infinitesimal, and  is a positive distance from any infinitesimals (since it is standard compact), we have

is a positive distance from any infinitesimals (since it is standard compact), we have

uniformly in  . Therefore

. Therefore  has no critical points near

has no critical points near  and so

and so  is holomorphic on

is holomorphic on  .

.

We first need a version of the fundamental theorem.

Lemma 4 Let  be a contour in

be a contour in  of length

of length  . Then

. Then

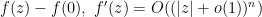

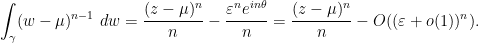

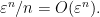

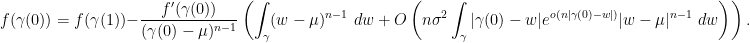

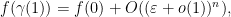

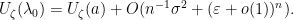

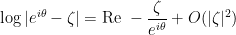

Proof: Our bounds on  imply that we can take the Taylor expansion

imply that we can take the Taylor expansion

of  in terms of

in terms of  , which is uniform in

, which is uniform in  . Taking expectations preserves the constant term (since it doesn’t depend on

. Taking expectations preserves the constant term (since it doesn’t depend on  ), kills the linear term, and replaces the quadratic term with a

), kills the linear term, and replaces the quadratic term with a  , thus

, thus

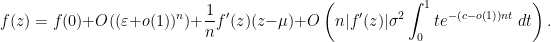

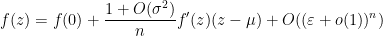

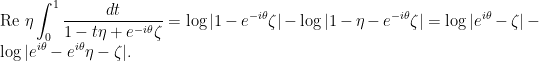

At the start of this series we showed

Plugging in the Taylor expansion of  we get

we get

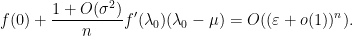

Simplifying the integral we get

whence the claim.

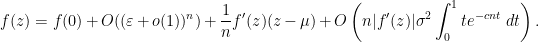

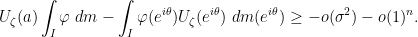

Lemma 5 Uniformly for  one has

one has

Proof: Applying the previous two lemmata we get

It remains to simplify

Taylor expanding  and using the self-similarity of the Taylor expansion we get

and using the self-similarity of the Taylor expansion we get

which gives that bound.

Lemma 6 Let  . Then

. Then

uniformly in  .

.

Proof: We may assume that  is small enough depending on

is small enough depending on  , since the constant in the big-

, since the constant in the big- notation can depend on

notation can depend on  as well, and

as well, and  only appears next to implied constants. Now given

only appears next to implied constants. Now given  we can find

we can find  from

from  to

to  which is always moving at a speed which is uniformly bounded from below and always moving in a direction towards the origin. Indeed, we can take

which is always moving at a speed which is uniformly bounded from below and always moving in a direction towards the origin. Indeed, we can take  to be a line segment which has been perturbed to miss the discrete set

to be a line segment which has been perturbed to miss the discrete set  , and possibly arced to miss

, and possibly arced to miss  (say if

(say if  is far from

is far from  ). By compactness of

). By compactness of  we can choose the bounds on

we can choose the bounds on  to be not just uniform in time but also in space (i.e. in

to be not just uniform in time but also in space (i.e. in  ), and besides that

), and besides that  is a curve through a compact set

is a curve through a compact set  which misses

which misses  . Indeed, one can take

. Indeed, one can take  to be a closed ball containing

to be a closed ball containing  , and then cut out small holes in

, and then cut out small holes in  around

around  and

and  , whose radii are bounded below since

, whose radii are bounded below since  is compact. Since the moments of

is compact. Since the moments of  are infinitesimal one has

are infinitesimal one has

Here we used  to enforce

to enforce

By the previous lemma,

Integrating this result along  we get

we get

Applying our preliminary bound, the previous paragraph, and the fact that  , thus

, thus

we get

We treat the first term first:

For the second term,  while

while  , so

, so  is bounded from below, whence

is bounded from below, whence

Thus we simplify

It will be convenient to instead write this as

Now we deal with the pesky integral. Since  is moving towards

is moving towards  at a speed which is bounded from below uniformly in “spacetime” (that is,

at a speed which is bounded from below uniformly in “spacetime” (that is, ![{K \times [0, 1]}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7BK+%5Ctimes+%5B0%2C+1%5D%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) ), there is a standard

), there is a standard  such that if

such that if  then

then

since  is going towards

is going towards  . (Tao’s argument puzzles me a bit here because he claims that the real inner product

. (Tao’s argument puzzles me a bit here because he claims that the real inner product  is uniformly bounded from below in spacetime, which seems impossible if

is uniformly bounded from below in spacetime, which seems impossible if  . I agree with its conclusion though.) Exponentiating both sides we get

. I agree with its conclusion though.) Exponentiating both sides we get

which bounds

Since  is standard, it dominates the infinitesimal

is standard, it dominates the infinitesimal  , so after shrinking

, so after shrinking  a little we get a new bound

a little we get a new bound

Since  is exponentially small in

is exponentially small in  , in particular it is smaller than

, in particular it is smaller than  . Plugging in everything we get the claim.

. Plugging in everything we get the claim.

4. Control on zeroes away from

After the gargantuan previous section, we can now show the “approximate level set” property that we discussed last time.

Lemma 7 Let  be a standard compact set which misses

be a standard compact set which misses  and

and  standard. Then for every zero

standard. Then for every zero  of

of  ,

,

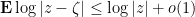

Last time we showed that this implies

Thus all the zeroes of  either live in

either live in  or a neighborhood of a level set of

or a neighborhood of a level set of  . Proof: Plugging in

. Proof: Plugging in  in the approximation

in the approximation

we get

Several posts ago, we proved  as a consequence of Grace’s theorem, so

as a consequence of Grace’s theorem, so  . In particular, if we solve for

. In particular, if we solve for  we get

we get

Using

plugging in  , and taking logarithms, we get

, and taking logarithms, we get

Now  and

and  misses the standard compact set

misses the standard compact set  , so since

, so since  we have

we have

(since  and

and  is infinitesimal). So we can Taylor expand in

is infinitesimal). So we can Taylor expand in  about

about  :

:

Taking expectations and using  ,

,

Plugging in  we see the claim.

we see the claim.

I’m not sure who originally came up with the idea to reason like this; I think Tao credits M. J. Miller. Whoever it was had an interesting idea, I think:  is a level set of

is a level set of  , but one that a priori doesn’t tell us much about

, but one that a priori doesn’t tell us much about  . We have just replaced it with a level set of

. We have just replaced it with a level set of  , a function that is explicitly closely related to

, a function that is explicitly closely related to  , but at the price of an error term.

, but at the price of an error term.

5. Fine control

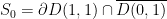

We finish this series. If you want, you can let  be a standard real. I think, however, that it will be easier to think of

be a standard real. I think, however, that it will be easier to think of  as “infinitesimal, but not as infinitesimal as the term of the form o(1)”. In other words,

as “infinitesimal, but not as infinitesimal as the term of the form o(1)”. In other words,  is smaller than any positive element of the ordered field

is smaller than any positive element of the ordered field  ; briefly,

; briefly,  is infinitesimal with respect to

is infinitesimal with respect to  . We still reserve

. We still reserve  to mean an infinitesimal with respect to

to mean an infinitesimal with respect to  . Now

. Now  by underspill, since this is already true if

by underspill, since this is already true if  is standard and

is standard and  . Underspill can also be used to transfer facts at scale

. Underspill can also be used to transfer facts at scale  to scale

to scale  . I think you can formalize this notion of “iterated infinitesimals” by taking an iterated ultrapower of

. I think you can formalize this notion of “iterated infinitesimals” by taking an iterated ultrapower of  in the theory of ordered rings.

in the theory of ordered rings.

Let us first bound  . Recall that

. Recall that  so

so  but in fact we can get a sharper bound. Since

but in fact we can get a sharper bound. Since  is discrete we can get

is discrete we can get  arbitrarily close to whatever we want, say

arbitrarily close to whatever we want, say  or

or  . This will give us bounds on

. This will give us bounds on  when we take the Taylor expansion

when we take the Taylor expansion

Lemma 8 Let  be standard. Then

be standard. Then

Proof: Let  be a standard compact set which misses

be a standard compact set which misses  and

and  a zero of

a zero of  . Since

. Since  (since

(since  is close to

is close to  ) and

) and  has positive standard part (since

has positive standard part (since  ) we can take Taylor expansions

) we can take Taylor expansions

and

in  about

about  . Taking expectations we have

. Taking expectations we have

and similarly for  . Thus

. Thus

since

Since

we have

Now  so

so  , whence

, whence

Now recall that  is uniformly distributed on

is uniformly distributed on  , so we can choose

, so we can choose  so that

so that

Thus

which we can plug in to get the claim.

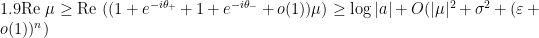

Now we prove the first part of the fine control lemma.

Lemma 9 One has

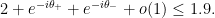

Proof: Let ![{\theta_+ \in [0.98\pi, 0.99\pi],\theta_- \in [1.01\pi, 1.02\pi]}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5Ctheta_%2B+%5Cin+%5B0.98%5Cpi%2C+0.99%5Cpi%5D%2C%5Ctheta_-+%5Cin+%5B1.01%5Cpi%2C+1.02%5Cpi%5D%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) be standard reals such that

be standard reals such that  . I don’t think the constants here actually matter; we just need

. I don’t think the constants here actually matter; we just need  or something. Anyways, summing up two copies of the inequality from the previous lemma with

or something. Anyways, summing up two copies of the inequality from the previous lemma with  we have

we have

since

That is,

Indeed,

so

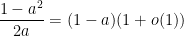

If we square the tautology  then we get

then we get

Taking expected values we get

or in other words

where we used the Taylor expansion

obtained by Taylor expanding  about

about  and applying

and applying  . Using

. Using

we get

Thus

Dividing both sides by ![{1 + \frac{1}{1.9 + o(1)} + o(1) \in [1, 2]}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B1+%2B+%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B1.9+%2B+o%281%29%7D+%2B+o%281%29+%5Cin+%5B1%2C+2%5D%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) we have

we have

In particular

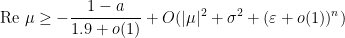

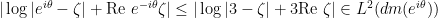

Now we treat the imaginary part of  . The previous lemma gave

. The previous lemma gave

Writing everything in terms of real and imaginary parts we can expand out

Using the bounds

(Which follow from the previous paragraph and the bound  ), we have

), we have

Since  is discrete we can find

is discrete we can find  arbitrarily close to

arbitrarily close to  which meets the hypotheses of the above equation. Therefore

which meets the hypotheses of the above equation. Therefore

Pkugging everything in, we get

Now  since

since  is infinitesimal; therefore we can discard that term.

is infinitesimal; therefore we can discard that term.

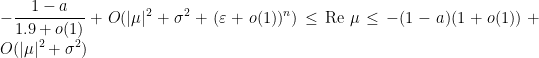

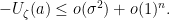

Now we are ready to prove the second part. The point is that we are ready to dispose of the semi-infinitesimal  . Doing so puts a lower bound on

. Doing so puts a lower bound on  .

.

Lemma 10 Let  be a standard compact set. Then for every

be a standard compact set. Then for every  ,

,

Proof: Since  is uniformly distributed on

is uniformly distributed on  , there is a zero

, there is a zero  of

of  with

with  . Since

. Since  , we can find an infinitesimal

, we can find an infinitesimal  such that

such that

and  . In the previous section we proved

. In the previous section we proved

Using  and plugging in

and plugging in  we have

we have

Now

Taking expectations,

Taking a Taylor expansion,

so by Fubini’s theorem

using the previous lemma and  we get

we get

We also have

since  is deterministic (and

is deterministic (and  , and

, and  ; very easy to check!) I think Tao makes a typo here, referring to

; very easy to check!) I think Tao makes a typo here, referring to  , which seems irrelevant. We do have

, which seems irrelevant. We do have

since  . Plugging in

. Plugging in

we get

I think Tao makes another typo, dropping the Big O, but anyways,

so by the triangle inequality

By underspill, then, we can take  .

.

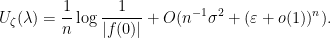

We need a result from complex analysis called Jensen’s formula which I hadn’t heard of before.

Theorem 11 (Jensen’s formula) Let  be a holomorphic function with zeroes

be a holomorphic function with zeroes  and

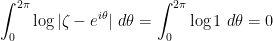

and  . Then

. Then

In hindsight this is kinda trivial but I never realized it. In fact  is subharmonic and in fact its Laplacian is exactly a linear combination of delta functions at each of the zeroes of

is subharmonic and in fact its Laplacian is exactly a linear combination of delta functions at each of the zeroes of  . If you subtract those away then this is just the mean-value property

. If you subtract those away then this is just the mean-value property

Let us finally prove the final part. In what follows, implied constants are allowed to depend on  but not on

but not on  .

.

Lemma 12 For any standard  ,

,

Besides,

Proof: Let  be the Haar measure on

be the Haar measure on  . We first prove this when

. We first prove this when  . Since

. Since  is discrete and

is discrete and  is compact, for any standard (or semi-infinitesimal)

is compact, for any standard (or semi-infinitesimal)  , there is a standard compact set

, there is a standard compact set

such that

By the previous lemma, if  then

then

and the same holds when we average in Haar measure:

We have

so, using the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality, one has

Meanwhile, if  then the fact that

then the fact that

implies

and hence

We combine these into the unified estimate

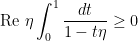

valid for all  , hence almost surely. Taking expected values we get

, hence almost surely. Taking expected values we get

In the last lemma we bounded  so we can absorb all the terms with

so we can absorb all the terms with  in them to get

in them to get

We also have

(here Tao refers to a mysterious undefined measure  but I’m pretty sure he means

but I’m pretty sure he means  ). Putting these integrals together with the integrals over

). Putting these integrals together with the integrals over  ,

,

By underspill we can delete  , thus

, thus

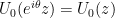

We now consider the specific case  . Then

. Then

Now Tao claims and doesn’t prove

To see this, we expand as

using Fubini’s theorem. Now we use Jensen’s formula with  , which has a zero exactly at

, which has a zero exactly at  . This seems problematic if

. This seems problematic if  , but we can condition on

, but we can condition on  . Indeed, if

. Indeed, if  then we have

then we have

which already gives us what we want. Anyways, if  , then by Jensen’s formula,

, then by Jensen’s formula,

So that’s how it is. Thus we have

Since  ,

,  , so the same is true of its expected value

, so the same is true of its expected value  . This gives the desired bound

. This gives the desired bound

We can use that bound to discard  from the average

from the average

thus

Repeating the Jensen’s formula argument from above we see that we can replace  with

with  for any

for any  . So this holds even if

. So this holds even if  is not necessarily nonnegative.

is not necessarily nonnegative.